What do Jesus’ words in Mat 12:40 teach us about the common notion that He was crucified on Friday? Think: how many nights are there from Friday until the first day of the week (Sunday) on which he was raised (Mat 28:1)? What day must He then have been crucified on, and how do we reconcile that with Luk 23:54 that says it was the preparation day and the Sabbath was about to begin? See Joh 19:14, 31, 42 and cf. Exo 12:16, Mat 27:62, Mar 15:42. Note: very significantly, in Luk 23:54 there are no definite articles in the Greek with preparation or Sabbath, as would be expected if Luke was referring to the usual day of preparation for the seventh day Sabbath—something our modern translations have missed being influenced by the common tradition that Jesus was crucified on Friday. Rather, as the Greek reads most literally, it was a day of preparation and a Sabbath was about to begin, namely the ceasing from work required by Exo 12:16 on the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread. This fell on the Friday before the seventh day Sabbath, and thus John rightly says “that Sabbath was a high day” (Joh 19:31).

If Jesus was crucified on Thursday which John clearly identifies as “the day of preparation for the Passover” (Joh 19:14), so that his death “about the 9th hour” (i.e., 3 pm, Mat 27:45-50) was exactly the time when the Passover lambs were being slain, and the Jews who led Jesus to the Praetorium did not enter “in order that they might not be defiled, but might eat the Passover” (Joh 18:28), how do we reconcile this with the accounts given in the synoptic gospels that Jesus had the previous evening (Wednesday) already eaten the Passover at which time He instituted the Lord’s Supper (Mat 26:17, 19; Mar 14:12-16; Luk 22:17-19)?? Hint: Observe that the first day of the month was determined by a new moon, the exact day of which is not always clear. Today, in order to establish consistency, a complex mathematical formula is often used to compute the new moon, but even by such means the consistency is not obvious[1], nor the result entirely without controversy. Throughout most of history the new moon and start of a new month was determined observationally as “the first visible crescent of the Moon, after conjunction with the Sun. This takes place over the western horizon in a brief period between sunset and moonset, and therefore the precise time and even the date of the appearance of the new moon by this definition will be influenced by the geographical location of the observer.” (Wickipedia, New Moon, 11/21/09). Even today,

The Islamic calendar has retained an observational definition of the new moon, marking the new month when the first Crescent Moon is actually seen, and making it impossible to be certain in advance of when a specific month will begin (in particular, the exact date on which Ramadan will begin is not known in advance). In Saudi Arabia, if the weather is cloudy when the new moon is expected, observers are sent up in airplanes. In Pakistan, there is a “Central Ruet-e-Hilal Committee” comprised of Ulemas (Religious Scholars), which takes help from 150 Observatories of Pakistan Meteorological Department all over the country and announces decision of the sighting of new moon. In Iran a special committee receives observations of every new moon to determine the beginning of each month. This committee uses one hundred groups of observers. (Wickipedia, New Moon, 11/21/09).

Since the new moon is not in the same state at the same time globally, the beginning and ending dates of Ramadan depend on what lunar sightings are received in each respective location. As a result, Ramadan dates vary in different countries… (Wickipedia, Ramadan, 11/26/09).

In this light, do you think there may have been controversy in Jesus’ day among religious authorities about when the new month began and consequently about what was actually the 14th day of the month on which the Passover was to be celebrated? Considering the huge influx of Jews from all over the ancient world for the Passover celebration (see Joh 12:20-23), is it possible that Jews from different locations may have understood the 14th of Nisan to fall on different days? Is it possible that different views of what day was actually the 14th of Nisan might have been tolerated in Jerusalem, in light of the logistics of sacrificing so many animals at the prescribed time on a single day?

The three synoptic Gospels are unanimous (Matthew 26:17, 19; Mark 14:12-16; Luke 22:17-19) in their statement that our Lord instituted the holy Eucharist in his last paschal supper. John is equally precise in saying that the Jews would not enter the judgment-hall “lest they should be defiled” through blood pollution, and be precluded from eating the Passover in the evening (John 18:28). How came it then, that our Lord should have celebrated the Passover on one evening, and that the Jews should have deferred the memorial feast till the corresponding period of the next day? We here give the following as a possible solution. Since the appearance of the new moon determined the Jewish calendar, an assembly was held in the Temple on the closing day of each month, to receive intelligence respecting the first phase of the new moon. If nothing was announced a day was intercalated, yet if the appearance of the moon was afterwards authenticated the intercalation was canceled. This naturally caused much confusion, especially in the critical month of Nisan. Hence (Talmud, Rosh Hash. 1) it was permitted that in doubtful cases the Passover might be observed on two consecutive days. For the intercalation could hardly be known in Galilee; and, according to Maimonides, in the more distant parts of Judaea the Passover was in some years kept on one day, at Jerusalem on another. Our Lord, coming in from the country, followed the letter of the law; but the main body of the Jews, observing rather the “tradition of the elders,” sacrificed the Passover on the following day in consequence of the intercalation of a day in the preceding month. Thus our Lord ate the Passover on the evening of the 14th Nisan, and was upon the same day “the very Paschal Lamb” by the death of the cross (Harvey, Creeds, p. 328, cited in McClintock and Strong Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature, Paschal Controversy).

To summarize, because of the ambiguity of what day was the first of the new month, the Passover on the 14th of the month could lawfully have been reckoned to fall either on Wednesday or Thursday evening. Jesus and His disciples observed it on the former, and so the synoptic authors of course emphasized their own Passover experience as the one Jesus partook of and because of its symbolism for the Lord’s Supper as the covenant meal for the New Covenant inaugurated by the blood of Christ. John, on the other hand, wrote much later and so had time to reflect upon the fullness of God’s timing and His sovereignty over the seasons that also allowed the 14th of the month to be reckoned by the religious leaders in Jerusalem to fall on Thursday, so that Christ our Passover lamb might also die for our sins at the exact time they were sacrificing the Passover lambs, which since the time of Moses had prefigured Him.

This timing is also significant because according to this reckoning “six days before the Passover”, which would have been on Friday, Nisan 8, John says that he came to Bethany (Joh 12:1), so that the supper Martha served Him that evening (Joh 12:2), the beginning of Nisan 9 (since Jews reckon the start of the day at evening), would have been a Sabbath meal, so that it was on that Saturday when “the great multitude therefore of the Jews learned that He was there; and they came…” (Joh 12:9). He then records that it was “on the next day”, Sunday, Nisan 10, that he made His triumphal entry into Jerusalem and was received by the multitudes with the praise of Psa 118:26, “Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord!” (Joh 12:12-13). This was in fulfillment of Exo 12:3 as the day upon which the Paschal Lamb was to be selected and “kept charge of” or “guarded” (cf. Mar 11:18, 12:12, 14:1-2) until the 14th when “the whole assembly of the congregation of Israel is to kill it at twilight (lit. between the two evenings)” (Exo 12:6, cf. Joh 18:38-40, 19:6,12-16, Mat 27:20-26), thus also fulfilling Psa 118:27 to “bind the festival sacrifice with cords to the horns of the altar” and Psa 118:22 that the builders would reject the stone that would become the chief cornerstone (cf. Mar 12:10-11). Interestingly, Psa 118 was the last hymn that was traditionally sung as part of the Passover feast and that Jesus sang with his disciples before leaving the last supper with his disciples for the Mount of Olives and Gethsemane where He was arrested (Mat 26:30,36)!

With this understanding we can now make much better sense of each account by the different gospel writers and the words they used to describe the timing of the Passover and Christ’s crucifixion that is otherwise quite confusing:

Matthew 27:62 “Now on the next day (after Christ was crucified, from the preceding context), which is the one after the preparation, the chief priests and the Pharisees gathered together with Pilate”.

It is clear from Matthew’s word choice that this day was not the Sabbath, otherwise he would have identified it as such, and not been so circuitous in his description. The day of preparation referred to was not that for the seventh day Sabbath, but for the Passover and the first day of unleavened bread as observed by the religious leaders in Jerusalem, which was the previous day, Thursday, the day Christ was crucified. Thus the day referred to was Friday.

Mark 15:42 “And when evening had already come, because it was the preparation day, that is, the day before the Sabbath…”

Here, as in Luk 23:54, there are no definite articles identifying that day as “the” preparation day for “the” Sabbath, but have been supplied by the translation because of the influence of the common notion that Jesus was crucified on Friday rather than Thursday. Most literally it reads, “When evening had already come, since it was a Preparation, which is a day before a Sabbath (prosa,bbaton)…”. The “Preparation” referred to was for the Passover and the first day of Unleavened Bread as observed by the religious leaders in Jerusalem on Thursday evening and Friday, on which no work could be done.

Luke 23:54 – 24:1 “And it was the preparation day, and the Sabbath was about to begin. Now the women who had come with Him out of Galilee followed after, and saw the tomb and how His body was laid. And they returned and prepared spices and perfumes. And on the Sabbath they rested according to the commandment. But on the first day of the week, at early dawn, they came to the tomb, bringing the spices which they had prepared.”

We have already noted that there are no definite articles in Luk 23:54 so that it reads most literally “it was a day of preparation, and a Sabbath was about to begin”. Again, the Sabbath referred to was not the seventh day Sabbath on Saturday, but the ceasing from work on the first day of Unleavened Bread required by Exo 12:16 which was observed by the religious leaders in Jerusalem on Friday. This Sabbath would still have had some impact upon those from Galilee who like Jesus had observed the Passover on Wednesday and the first day of Unleavened Bread on Thursday. Thus “the women who had come with Him out of Galilee” and had already observed in their hearts the required rest on Thursday and so had no moral compunction about preparing spices and perfumes on that Friday, as it was not for them a Sabbath, would still have been prevented from attending to the body of Jesus since that day was officially observed as a Sabbath in Jerusalem. For to do so would have been to cause even further offense to those who had been seeking to destroy Jesus for this very thing (Mat 12:14 and preceding context) and had just succeeded in finally doing so.

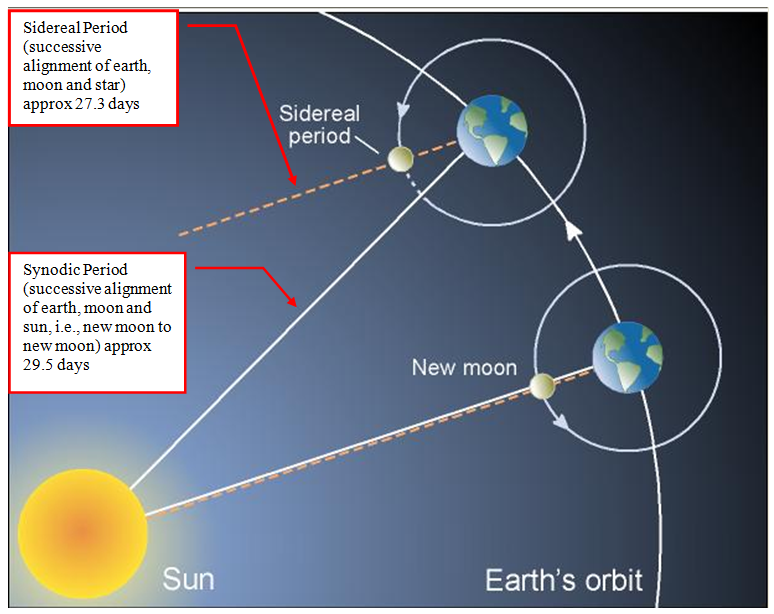

1. “The time interval between new moons—a lunation—is variable. The mean time between new moons, the synodic month, is about 29.53 days… Periodic perturbations change the time of true conjunction from these mean values. For all new moons between 1601 and 2401, the maximum difference is 0.592 days = 14h13m in either direction. The duration of a lunation (i.e. the time from new moon to the next new moon) varies in this period between 29.272 and 29.833 days.” (Wickipedia, New Moon, 11/21/09). For 2010, the number of days between new moons as indicated on one calendar is found to be: 30, 30, 29, 30, 30, 29, 29, 30, 29, 29, 30, 29.↩