Contrary to Judas’ expectations, Jesus was condemned to death by the Sanhedrin and delivered up to Pilate for execution. Unable to see any victory through suffering, or life through death, he could not imagine that Jesus would allow Himself to be crucified. Faced with the gravity of his error that would make him accountable for betraying the Son of God unto death, he quickly tried to undo his deed by returning the money to the Jewish leaders and confessing his sin that Jesus was innocent and he had betrayed Him. But supposing they could escape any responsibility for Jesus’ death by pinning it on Judas’ betrayal, they wouldn’t accept it and turned him away, thus adding to their sin not only the continued prosecution unto death of Jesus in spite of Judas’ confession, but the despair unto death to which it drove him[1]. What does the pickle in which Judas found himself, and that the religious leaders would in time come to share, illustrate about the truth of Pro 13:15, “The way of the treacherous is hard”?

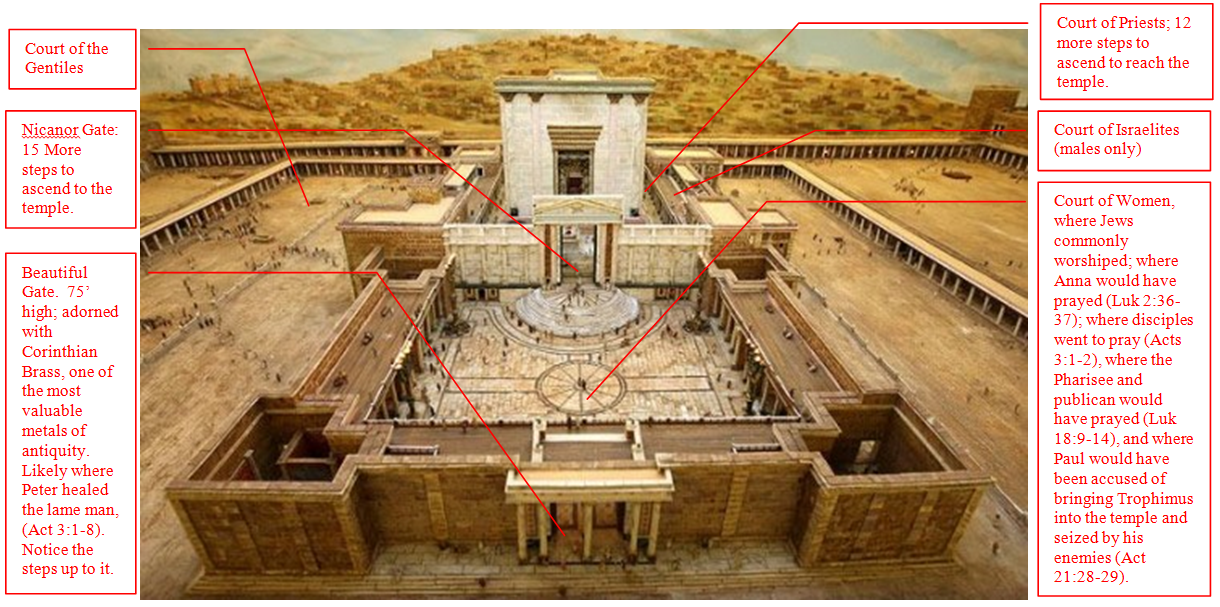

Because the religious leaders would not take back the money to undo Judas’ deed, what does Matthew record that he did? See Mat 27:5. Does Matthew say where in the temple Judas cast the 30 pieces of silver? Note that the word used is not the generic word for temple, ἱερός, that includes all the surrounding courts, but the more specific ναός, that refers to the sanctuary itself that consisted of both the holy of holies as well as the holy place where the priests ministered. Hence, the NAS translates it as the sanctuary, or temple sanctuary, whereas the KJV has simply temple. Note also that he cast, or even cast down as the word often connotes, the money into the sanctuary, so that he didn’t enter it himself, which was unlawful, and so that only the priests would have had access to it; see Mat 27:6. Note also that the word for departed carries the connotation of fleeing or escaping a potential danger, as it is commonly used in the LXX; see Exo 2:15 and cf. Mat 2:12-14,22, 4:12, 9:24, 12:15, 14:13, 15:21, Mar 3:7, and Joh 6:15 for all the other gospel occurrences of this word. What does the use of this word here indicate about the manner in which Judas left the temple after throwing the silver into the sanctuary? What fear may have motivated such a hasty retreat? Think: Would not casting anything into the sanctuary have easily been interpreted as profaning it?

Consider the money that earlier glittered so brightly before Judas that he was blind to its end, but that now was so repugnant to him that he could no longer hold onto it and had to cast it away; what does this teach us about the curse of ill-gotten gain, as well as the vain emptiness of the world’s riches? Cf. Jos 7:11-12,21, 1Ki 21:19, 2Ki 5:20-27, Hab 2:9, Mat 16:26, Jam 5:1-4. Although we live in a time of opulence when such wealth has caused so many to forget God and to indulge their lusts, what does Judas’ example also remind us about the vanity of worldly gain and the similar hopeless end of all whose hope is in it rather than in God? Cf. Deut 8:11-14, Pro 23:4-5, Luk 12:13-21, 1Ti 6:8-10, Rev 18:7-8.

Having gambled on what he assumed was a sure bet, only to discover that it wasn’t, and that his reward was a worthless bauble compared to the real riches of truth, righteousness, faithfulness, love, and fidelity that he had traded for it, what does Matthew further record that Judas did in Mat 27:5?  Again, what does this remind us about the ultimate anguish and despair of those who trade the true riches of heaven for the false riches of the world? Although tempting, should we ever trade even ill-treatment with the people of God for the passing pleasures of sin? What does the author of Hebrews remind us about the reproach of Christ compared to even the treasures of Egypt? See Heb 11:24-26.

Again, what does this remind us about the ultimate anguish and despair of those who trade the true riches of heaven for the false riches of the world? Although tempting, should we ever trade even ill-treatment with the people of God for the passing pleasures of sin? What does the author of Hebrews remind us about the reproach of Christ compared to even the treasures of Egypt? See Heb 11:24-26.

How does Matthew’s description of Judas’ end compare with that of Luke in Acts 1:18? Are the two accounts necessarily contradictory? How can they be reconciled? Notice in Acts 1:18 that falling headlong only occurs here in the New Testament, but is found 4 times in the LXX with the basic meaning of to the ground, such as leveled to the ground, or prostrate to the ground; see 3Ma 5:43,50, 6:23[2]; it is also possible that the word in this context has the medical meaning of swollen or distended. Falling is also not the word typically used for falling from a height (πίπτω), but is actually γίνομαι, that means to happen, or come to be, and in spite of occurring over 600 times in the New Testament, is only translated as falling here. Hence, in contrast to Matthew’s account that describes the end of Judas’ life by hanging, Luke describes the grisly and accursed end of his body. I.e., however it happened—whether it was cut down when it was discovered or the rope or cord used to hang himself eventually broke—his corpse came to be level with the ground, and as a consequence it burst open in the middle and all his bowels gushed out.

Why is it not unlikely that Judas’ corpse was not discovered until at least Sunday? Recall that it was Thursday, a required sabbath for those like Jesus and His followers who had celebrated the Passover the night before so it was the first day of Unleavened Bread, and Friday would be the first day of Unleavened Bread for those celebrating the Passover later that day and hence a required sabbath, followed by Saturday which was the seventh day sabbath. What effects to a hanging corpse naturally occur that could lead to the end described by Luke? Note: a decomposing body causes gases to build up and increase pressure in the body, so that within 3 to 5 days it begins to bloat up to as much as twice in size; the internal pressure on such corpses has even been known to cause them to explode. Yikes! What then does Luke’s description indicate about how long Judas’ body had hung there? How does this contrast with Jesus’ body that was taken down from the tree upon which He was hanged and laid in a tomb, so as to not remain on the cross due to the Passover (Joh 19:31)? See Mat 12:40; cf. Deut 21:23, Jos 10:26-27. In what way did that which happened to Judas’ corpse reflect the sinfulness of his life, even as that which happened to Jesus’ corpse reflected the righteousness of his life? Cf. 1Ki 13:1-30, 21:23-24, 2Ki 9:35, 13:20-21, Jer 22:19, 36:30. What does this remind us about the sacredness of our human bodies as the earthly dwelling place of a soul created in the image of God, and thus the importance of treating them with respect even after physical death—and especially those of the righteous? How does this also help us understand the traditional Christian repulsion for cremation, and why the Roman Catholic Church would even exhume and burn to ashes the dead bodies of those it deemed to be heretics? See again 1Ki 13:1-2. What does the fact that the hypocritical religious leaders saw the need for a burial place for strangers in purchasing the Potter’s Field (Mat 27:7) indicate about their concern that even foreigners be afforded a proper burial as opposed to cremation or simply dumping them in a place of refuse?

[1] If Judas had gone to Christ, or to some of the disciples, perhaps he might have had relief, bad as the case was; but, missing of it with the chief priests, he abandoned himself to despair: and the same devil that with the help of the priests drew him to the sin, with their help drove him to despair. Matthew Henry.

[2] 3 Maccabees 5:43 …and would also march against Judea and rapidly level it to the ground with fire and spear.

3 Maccabees 5:50 Not only this, but when they considered the help that they had received before from heaven, they prostrated themselves with one accord on the ground, removing the babies from their breasts,

3 Maccabees 6:23 For when he heard the shouting and saw them all fallen headlong to destruction (i.e., leveled to the ground), he wept and angrily threatened his Friends.