Matthew 14:1 Who was the Herod mentioned in this verse, why is he called a tetrarch, and what was his relationship to the other Herods mentioned in Scripture? Note: the Herod mentioned here was surnamed Antipas. It was his father, Herod the Great, who established the Herodian dynasty, was king when Jesus was born (Mat 2:1), and slew all the children in and around Bethlehem. Herod the Great was an Idumean of Edomite descent and hence a descendent of Esau and not a true Jew; with the help of the Romans he usurped the previous Hasmonean dynasty that had ruled from the time of the Maccabbees described in the Apocrypha. With great cruelties he secured his reign and established and maintained the Pax Romana. Yet in Roman fashion he was also noted as a superb builder who improved his domains with modern cities and magnificent public works after the manner of a second Solomon. In the eyes of both the supreme world authority at the time and those in his favor who benefited from his reign he was thus the king of the Jews and given that title. To ingratiate himself to the Jews who despised him for his servility to Rome and allowing heathen customs to flourish he set about building a temple even more magnificent than that of Solomon’s. Begun in 21 BC it was not completely finished until 65 AD during the reign of Herod Agrippa II (cf. Joh 2:20)—five years before it was destroyed by the Romans.

Some things to think about: In what many ways then was Herod the Great and the dynasty he established a counterfeit of the expected Messiah and the kingdom He would establish?[1] Compare and contrast his reign and the nature of his kingdom with that of Jesus. How would the stark contrast of his reign with what they expected of the Messiah’s reign have forced people to decide in their hearts what sort of king they wanted: a king after the manner of the world, or a return to the reign of God Himself?[2] Is it any different today? How would Herod’s reign have prepared the hearts of those who loved the truth for the true King of the Jews?

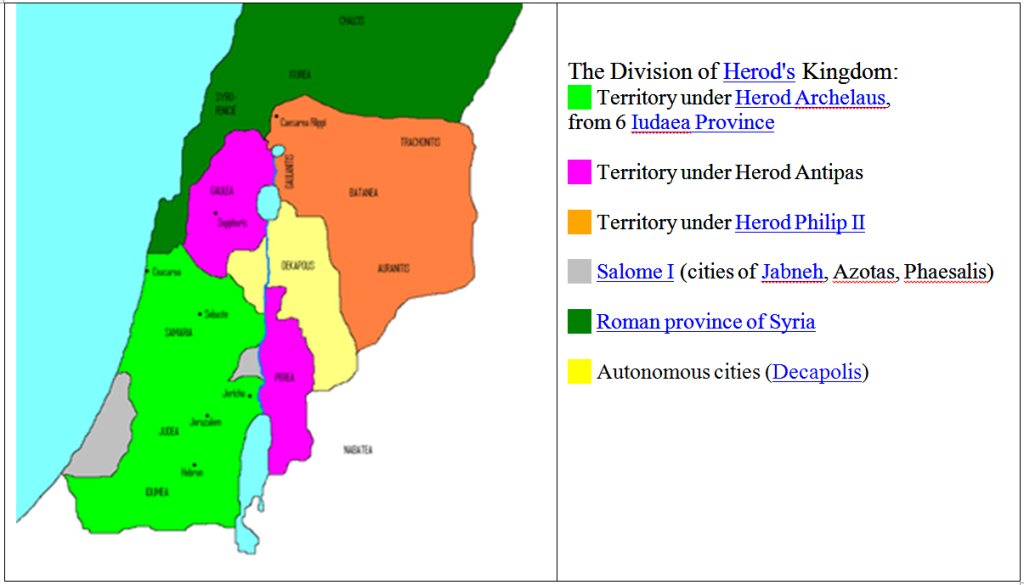

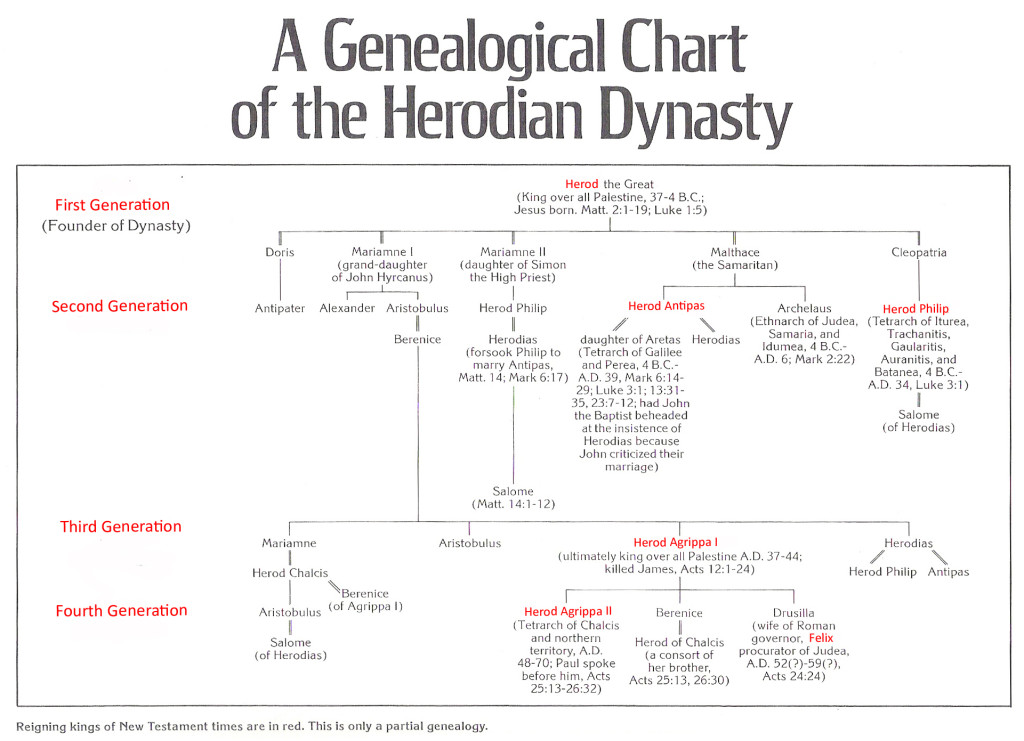

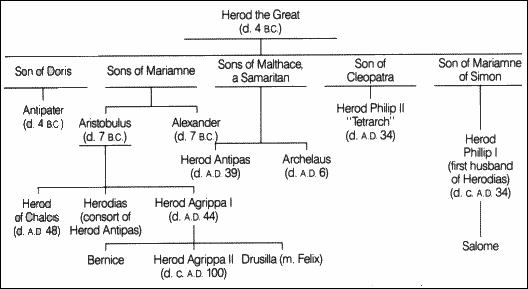

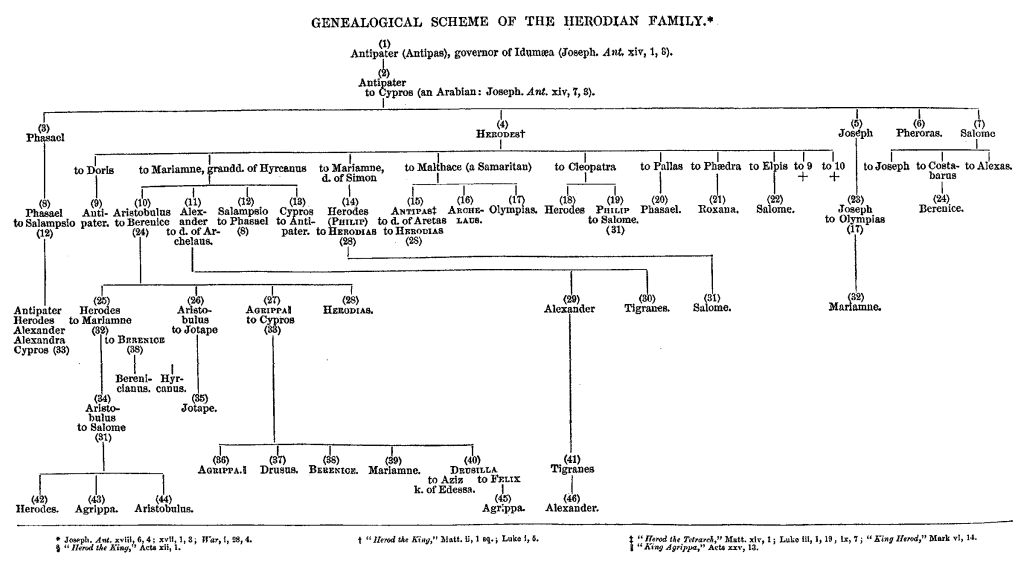

After Herod the Great’s death in 4 BC his kingdom was divided between Antipas and Antipas’ full brother Archelaus whose mother was a Samaritan woman named Malthace, and his half-brother Philip II whose mother was Cleopatra of Jerusalem. The younger Archelaus became ethnarch of a larger, more significant portion of the kingdom consisting of Judea, Samaria and Idumea (ancient Edom) because of a last-minute change in his father’s will. Like his father before him, he was noted for his cruelty (cf. Mat 2:22) and was deposed in 6 AD because of it, after which Judea was then governed by Roman procurators (one of which was Pilate). Antipas and Philip along with a Lysanias became tetrarchs ruling over smaller portions of their father’s kingdom: Antipas over Galilee and Perea, Philip over a region east of there in modern Syria, and Lysanias in Abilene near Damascus; cf. Luk 3:1. Antipas, in addition to putting John the Baptist to death, was the Herod to whom Pilate would send Jesus a few years later hoping to escape having to condemn a man in whom he found no guilt, in order to keep peace with the Jews who wanted Him put to death (Luk 23:7-12, Act 4:27).

Herodias was a granddaughter of Herod the Great; her father was Aristobulus, another son of Herod the Great by Mariamne I, herself a granddaughter of John Hyrcanus who was a ruler and high priest in the previous Hasmonean dynasty. Though passionately fond of Mariamne who was described as the most beautiful princess of the age, Herod ultimately had both her and Aristobulus put to death for fear that because of their Hasmonean descent they were plotting against his rule. Herodias was thus of both Hasmonean and Herodian descent and became the wife of Herod Philip I—not the tetrarch, but another son of Herod the Great by a different Mariamne who was the daughter of Simon the high priest; thus he would have been her half-uncle as both of the Philips and Antipas were half-brothers of her father Aristobulus. Philip I had been disinherited by his father and so had no kingdom, which likely figured in to Herodias divorcing him to marry Antipas. Antipas himself was married to a daughter of Aretas king of Arabia, whom he divorced in favor of Herodias. As a result, Aretas invaded the dominions of Antipas and defeated him with great loss. Josephus relates that the Jews believed this defeat was a punishment from God for having imprisoned and put to death John the Baptist[3].

The daughter of Herodias and Philip I who danced before and pleased Herod Antipas (who would have been her stepfather) was named Salome; she later married Herod Philip the Tetrarch who was thus her paternal half-uncle.

Herodias’ brother (and hence grandson of Herod the Great through Aristobulus whom he had put to death) was Herod Agrippa I, surnamed Agrippa the Great by Josephus. Living in Rome earlier in life he was forced to flee due to a huge debt incurred by luxurious living. Later he was imprisoned in Rome for speaking against the emperor Tiberius in favor of Gaius (Caligula). However, his fortunes reversed when Gaius did become emperor in 37 a.d. Gaius released him from prison and gave him the tetrarchy of his half-uncle Philip who had died childless in 34 a.d., as well as the title of king. Indignant that the royal title had been given to her brother over her new husband, Herodias persuaded Antipas to go to Rome in 38 a.d. and appeal to the emperor for the kingly title. However, Agrippa who had already received the title and was in favor with the emperor opposed it with the result that Antipas was banished to Gaul and his tetrarchy also given to Agrippa. Herodias followed him into exile and he eventually died in Spain. What does the example of Herod Antipas teach us about the just rewards of pride and selfish ambition? See Job 4:8, Pro 1:31, 16:18, 22:8, Isa 3:10-11, Jer 2:19, Gal 6:7-8. In 41 a.d., for having assisted Claudius who succeeded Gaius as emperor Agrippa was also given the rule over Judea and Samaria as well as the tetrarchy of Lysanias (Luk 3:1), so that he now possessed the entire kingdom of his grandfather Herod the Great.

Unlike Antipas and the other Herodians who did not reside in Jerusalem and were Jewish only in name and for political reasons, Agrippa loved Jerusalem and strictly observed the laws of the Jews. This together with the political expediency of placating the majority to maintain peace accounts for his persecution of the Christians: it was this Herod who around 44 a.d. “laid hands on some who belonged to the church, in order to mistreat them”. He “had James the brother of John put to death with a sword”, and “proceeded to arrest Peter also” (Act 12:1-3). Peter was miraculously delivered from Agrippa’s prison and the four squads of soldiers he had guarding him on the very night before he was to be brought forth after the Passover for execution (Act 12:4-19). Shortly after this Agrippa I was struck dead by God, just a few years into his reign over the entire kingdom (Act 12:20-23). What does this teach us about how all of man’s plans to establish himself will prevail when they conflict with God’s?

Agrippa I had three children that are mentioned in Scripture. Herod Agrippa II was only 17 when his father died and so the Romans, supposing him too young to rule his father’s kingdom, made it again a Roman province and appointed a Roman procurator. Four years later the emperor Claudius gave him the small kingdom of Chalcis that was vacated by the death of Herod Chalcis who had married Mariamne, a sister of Herodias and Agrippa I. Four years after this Claudius took this away and gave him instead the larger tetrarchies of Philip and Lysanias and the title of king. Nero later added to these dominions. Agrippa’s sister was named Bernice; she was also married to Herod Chalcis who died in 48 a.d. and whose small kingdom her brother was appointed to rule. When her husband died, she lived with her brother in a supposed incestuous relationship, which caused a scandal so that she was induced to marry Polemon (a Ptolemy), the king of Cilicia, which marriage did not last and she eventually returned to her brother. It was before this Agrippa II and his sister Bernice that Paul gave his defense at the request of Festus in Acts 25-26 (see Acts 25:13,23, 26:30). Another sister of this Agrippa II was Drusilla; she was married to Azizus king of Edessa. Celebrated for her beauty and envied by her older sister Bernice, she was induced by the Roman governor Felix to divorce her husband and marry him who would be able to better protect her from her sister’s jealousy . It was before this Felix and his wife Drusilla that Paul spoke about “righteousness, self-control and the judgment to come” so that “Felix became frightened” (Act 24:24-25). Drusilla had a son by Felix who was also named Agrippa and who perished in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 a.d.

In the Jewish rebellion that culminated in the fall of Jerusalem and demise of the Jewish nation Agrippa II sided with the Romans and warned the Jews that resistance was futile. Bernice consorted with both Vespasian, who became emperor, and his son Titus, the Roman general who destroyed Jerusalem, and who would have married her except for offending the Romans. With the fall of the Jewish nation Agrippa’s kingdom also fell, and following the war the Romans rewarded his loyalty so that he became a praetor in Rome where he lived with Bernice until his death in 100 a.d.

What does the Herodian dynasty teach us about the ungodly world of politics that prevailed in the time of Jesus as compared to the politics that prevail today? What does it teach us about the fundamental difference between the kingdoms of the world and the kingdom Jesus came to establish? Think: who is king in God’s kingdom, and who is king in a worldly kingdom? Cf. 1Sa 8:4-22. Will the kingdom of God that is marked by righteous and peace ever be established by the governments of men? See Dan 2:31-45. Why is that? Think: who is the ultimate ruler of the kingdoms of this age? See Luk 4:5-6, Joh 12:31, 14:30, 2Co 4:4, Eph 2:2, 1Jo 5:19. What does this teach us about the corrupting influence of political power, and why it is so corrupting? Would a “Christian” government be any different? In light of this truth and the lessons of history, what did our nation’s founders do to limit the corrupting influence of political power? What should we as Christians in this age seek in regard to a government? How might a Christian politician guard himself against the corrupting influence of his office?

1. The history of the Herodian family presents one side of the last development of the Jewish nation. The evils which had existed in the hierarchy that grew up after the Return, found an unexpected embodiment in the tyranny of a foreign usurper. Religion was adopted as a policy; and the Hellenizing designs of Antiochus Epiphanes [who set up a literal abomination of desolation in the temple and offered sacrifice there to Jupiter Olympias, cf. Dan 11:31-32] were carried out, at least in their spirit, by men who professed to observe the law. Side by side with the spiritual “kingdom of God” proclaimed by John the Baptist, and founded by the Lord, a kingdom of the world was established, which in its external splendor recalled the traditional magnificence of Solomon. The simultaneous realization of the two principles, national and spiritual, which had long variously influenced the Jews, in the establishment of a dynasty and a church, is a fact pregnant with instruction. In the fullness of time a descendant of Esau established a false counterpart of the promised glories of the Messiah (McClintock and Strong’s Cyclopedia; Herod)… The Idumeans were conquered and brought to Judaism by John Hyrcanus, 130 B.C. Thus the Herods, though aliens by birth, were Jews in faith. They made religion an engine of state policy. Eschewing Antiochus Epiphanes’ design to Graecize Jerusalem by substituting the Greek worship and customs for the Jewish law, the Herod’s, while professing to maintain the law, as effectively set at naught its spirit by making it a lever for elevating themselves and their secular kingdom. For this end Herod adorned gorgeously the temple with more than Solomonic splendor. Thus a descendant of Esau tried still to get from Jacob the forfeited blessing (Gen. 27:29,40), in vain setting up an earthly kingdom on a professed Jewish basis, to rival Messiah’s spiritual kingdom, as it was then being fore-announced by John Baptist. The “HERODIANS” probably cherished hopes of Herod’s kingdom becoming ultimately, though at first necessarily leaning on Rome, an independent Judaic eastern empire. The Jewish religion thus degraded into a tool of ambition lost its spiritual power, and the theocracy becoming a lifeless carcass was the ready prey for the Roman eagles to pounce upon and destroy (Mt. 24:28). (Fausett’s Bible Dictionary, Herod).↩

2. The diversity of Herod’s nature is remarkable. On regarding his magnificence, and the benefits he bestowed upon his people, one cannot deny that he had a very beneficent disposition; but when we read of his cruelties, not only to his subjects, but even to his own relations, one is forced to allow that he was brutish and a stranger to humanity (comp. Josephus, Ant. 16, 5, 4). His servility to Rome is amply shown by the manner in which he transgressed the customs of his nation and set aside many of their laws, building cities and erecting temples in foreign countries, for the Jews did not permit him so to do in Judaea, even though they were under so tyrannical a government as that of Herod. His confessed apology was that he was acting to please Caesar and the Romans, and so through all his reign he was a Jewish prince only in name, with a Hellenistic disposition (comp. Josephus, Ant. 15, 9, 5; 19:7, 3). It has even been supposed (Jost, Gesch. d. Judenth. 1, 323) that the rebuilding of the Temple furnished him with the opportunity of destroying the authentic collection of genealogies which was of the highest importance to the priestly families. Herod, as appears from his public designs, affected the dignity of a second Solomon, but he joined the license of that monarch to his magnificence; and it was said that the monument which he raised over the royal tombs [of David and Solomon] was due to the fear which seized him after a sacrilegious attempt to rob them of secret treasures (Josephus, Ant. 16, 7,1). He maintained peace at home during a long reign by the vigor and timely generosity of his administration. Abroad he conciliated the goodwill of the Romans under circumstances of unusual difficulty. His ostentatious display, and even his arbitrary tyranny, was calculated to inspire Orientals with awe. Bold and yet prudent, oppressive and yet profuse, he had many of the characteristics which make a popular hero; and the title [i.e., the Great] which may have been first given in admiration of successful despotism now serves to bring out in clearer contrast the terrible price at which the success was purchased. (McClintock and Strong’s Cyclopedia; Herod).↩

3. Antiquities of the Jews 18:109-119 109 About this time Aretas (the king of Arabia Petrea) and Herod had a quarrel, on the account following:–Herod the tetrarch had married the daughter of Aretas, and had lived with her a great while; but when he was once at Rome, he lodged with Herod, {a} who was his brother, indeed, but not by the same mother; for this Herod was the son of the high priest Simon’s daughter. 110 However, he fell in love with Herodias, this last Herod’s wife, who was the daughter of Aristobulus their brother, and the sister of Agrippa the Great. This man ventured to talk to her about a marriage between them; which address, when she admitted, an agreement was made for her to change her habitation, and come to him as soon as he should return from Rome: one article of this marriage also was this, that he should divorce Aretas’ daughter. 111 So Antipas, when he had made this agreement, sailed to Rome; but when he had done there the business he went about, and was returned again, his wife having discovered the agreement he had made with Herodias, and having learned it before he had notice of her knowledge of the whole design, she desired him to send her to Macherus, which is a place in the borders of the dominions of Aretas and Herod, without informing him of any of her intentions. 112 Accordingly Herod sent her there, as thinking his wife had not perceived anything; now she had sent a good while before to Macherus, which was subject to her father and so all things necessary for her journey were made ready for her by the general of Aretas’ army; and by that means she soon came into Arabia, under the conduct of the various generals, who carried her from one to another successively; and she soon came to her father, and told him of Herod’s intentions. 113 So Aretas made this the first occasion of his enmity between him and Herod, who had also some quarrel with him about their borders of the country of Gamalitis. So they raised armies on both sides, and prepared for war, and sent their generals to fight instead of themselves; 114 and, when they had joined battle, all Herod’s army was destroyed by the treachery of some fugitives, who, though they were of the tetrarchy of Philip, joined with Aretas’ army. 115 So Herod wrote about these affairs to Tiberius; who being very angry at the attempt made by Aretas, wrote to Vitellius to make war upon him, and either to take him alive, and bring him to him in bonds, or to kill him, and send him his head. This was the charge that Tiberius gave to the governor of Syria. 116 Now some of the Jews thought that the destruction of Herod’s army came from God, and that very justly, as a punishment of what he did against John, that was called the Baptist; 117 for Herod slew him, who was a good man, and commanded the Jews to exercise virtue, both as to righteousness toward one another, and piety toward God, and so to come to baptism; for that the washing [with water] would be acceptable to him, if they made use of it, not in order to the putting away [or the remission] of some sins [only], but for the purification of the body: supposing still that the soul was thoroughly purified beforehand by righteousness. 118 Now, when [many] others came in crowds about him, for they were very greatly moved [or pleased] by hearing his words, Herod, who feared lest the great influence John had over the people might put it into his power and inclination to raise a rebellion, (for they seemed ready to do anything he should advise,) thought it best, by putting him to death, to prevent any mischief he might cause, and not bring himself into difficulties, by sparing a man who might make him repent of it when it would be too late. 119 Accordingly he was sent as prisoner, out of Herod’s suspicious temper, to Macherus, the citadel I before mentioned, and was there put to death. Now the Jews had an opinion that the destruction of this army was sent as a punishment upon Herod, and a mark of God’s displeasure to him.↩

Pingback: 新約時期 The New Testament Period:希律王朝的統治 Herodian dynasty | 耶路撒冷聖殿 Temple of Jerusalem – Live by Faith, Not By Sight