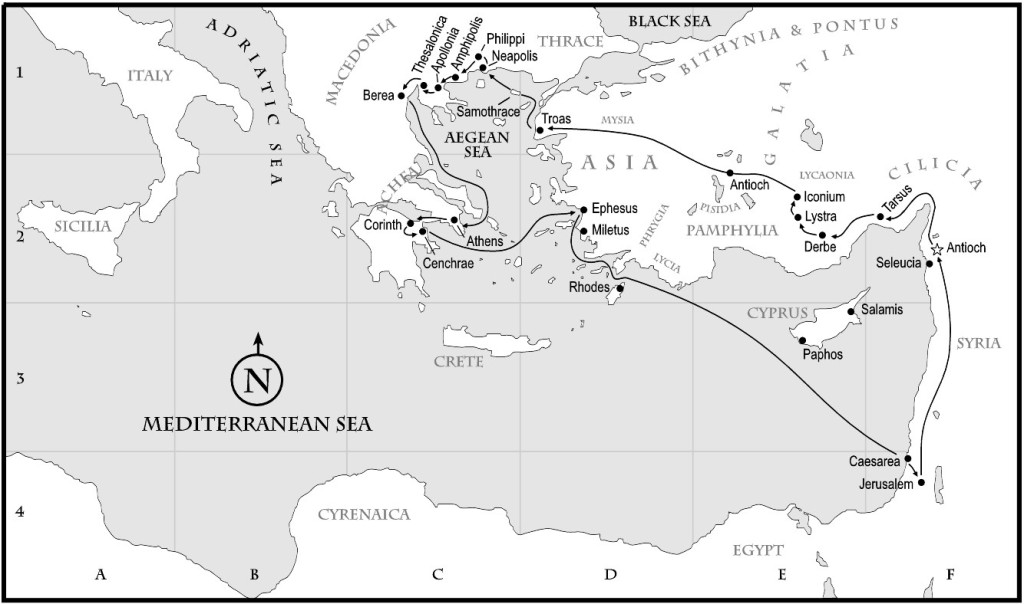

Recall in this parable that those who were originally invited to the wedding feast of the king’s son were considered unworthy because they stubbornly and arrogantly refused to come; what did the king in the parable then command his servants? See Mat 22:9. Who did those represent who would now be invited to come? See Act 8:1-5, 11:19-20,25-26, 13:45-46, Rom 11:25; cf. Eph 2:11-13. Did the king say to go into the remote districts and search out the hermits who lived off the beaten path in caves and holes in the ground? Where did the king command his slaves to go to find them? Note that the NAS “main highways” translates “diexodous ton hodon” which means literally the “ways through which ways go out” and refers to the major arteries or roadways that go out of a city from which other smaller roadways would branch off. What does this teach us about an important missions strategy? What do those “main highways” represent in terms of major locations from which the gospel would most quickly disseminate? How did the early church’s and especially Paul’s missionary endeavors reflect this very pattern? Cf. Act 8:5[1], Act 11:22[2], Act 13:4-5[3], Act 13:13[4], Act 13:14[5], Act 14:1[6], Act 14:6[7], Act 16:12[8]>, Act 17:1[9], Act 17:16[10], Act 18:1[11], Act 19:1[12], Rom 1:7-13[13]. Consider too that the cities of Laodicea and Colossae were off the beaten path where Paul had not actually visited, but the churches there were established and strengthened as a result of his ministry in Ephesus. What does this Biblical example teach us about how serious the early church was about the Lord’s command to herald the gospel message to all mankind and the purposeful intent with which they went about doing it? Cf. Act 17:6, Rom 15:19, Col 1:23. In what ways are Christians today similarly purposeful, and how might we be?

For what ultimate reason did the king in the parable direct his servants to the major thoroughfares to invite as many as they found there to the wedding feast he had prepared for his son? Was it because he was not as concerned with those who were off the beaten path, or because it would be easier with so many on the main highways to find a few who were worthy of his kingly beneficence? See Mat 22:10 as well as Luk 14:21-23. What does this again remind us about God’s earnest desire to have fellowship and communion with people and His willingness to supply every provision and bless any and all who will but come in order that His house may be filled? Cf. Eze 18:23, 1Ti 2:1,3-4, 2Pe 3:9. Is God’s desire any different today for the wedding hall to be filled with guests with whom He may commune? Is there any doubt that God is willing for us to come? Notice that it isn’t a matter of whether or not God is willing, but are we willing? Are we? Considering that the king’s directive towards the main highways was not to exclude any who weren’t found there but as the means to most effectively communicate his desire for all who were willing to come, what does this also teach us about man’s responsibility in relation to other men: not only to share with others who are more remote the open invitation we have been fortunate enough to hear, but to also be concerned enough about our own souls to be alert and seek truth that God disseminates through more major thoroughfares?

1. Samaria was a large and important city that Herod “adorned … on a scale of great magnificence, calling it Sebaste in honor of the emperor (ISBE).↩

2. Antioch was the capital of the Roman province of Syria; it was the “queen of the East,” the third city, after Rome and Alexandria, of the Roman world. ↩

3. Salamis was the most populous and flourishing town of Cyprus in the Hellenic and Roman periods (ISBE).↩

4. Perga was the chief city in Pamphylia in Asia Minor.↩

5. Pisidian Antioch was a Roman colony that became the capital of southern Galatia and the chief of a series of military colonies founded by Augustus.↩

6. Iconium was one of the chief cities in the southern part of the Roman province Galatia (ISBE).↩

7. Lystra was a Roman colony and in the time of Paul a center of education and enlightenment. Derbe was a city on the frontier of Roman territory on a great Roman road leading from Southern Galatia to the East, where commerce entering the province had to pay the customs dues. (ISBE). Interestingly, Paul stopped at Derbe and did not venture further into non-Roman territory.↩

8. Besides being a major city of Macedonia, Philippi lay on the Egnatian Way, the major east/west Roman road across northern Greece stretching from the Adriatic on the west to Byzantium (later Constantinople) in the east.↩

9. Thessalonica also lay on the Egnatian Way and was a large and populous city and the capital of one of the districts of Macedonia.↩

10. Athens was the capital of Attica, the Greek center of culture.↩

11. Corinth was the capital of Achaia and the seat of the Roman proconsul; it was also famous for its commerce, being situated on the isthmus connecting the Peloponnese with Greece and having harbors in both the Ionian and Aegean seas.↩

12. Ephesus was the capital of Asia. “With an artificial harbor accessible to the largest ships, and rivaling the harbor at Miletus, standing at the entrance of the valley which reaches far into the interior of Asia Minor, and connected by highways with the chief cities of the province, Ephesus was the most easily accessible city in Asia, both by land and sea. Its location, therefore, favored its religious, political and commercial development, and presented a most advantageous field for the missionary labors of Paul.” (ISBE).↩

13. As the capital of the Roman empire Rome was the most strategic hub for the dissemination of the gospel because of its communication and travel links to everywhere in the empire. Consider the saying, “all roads lead to Rome”, which means that in the other direction they therefore lead everywhere else.↩